Background

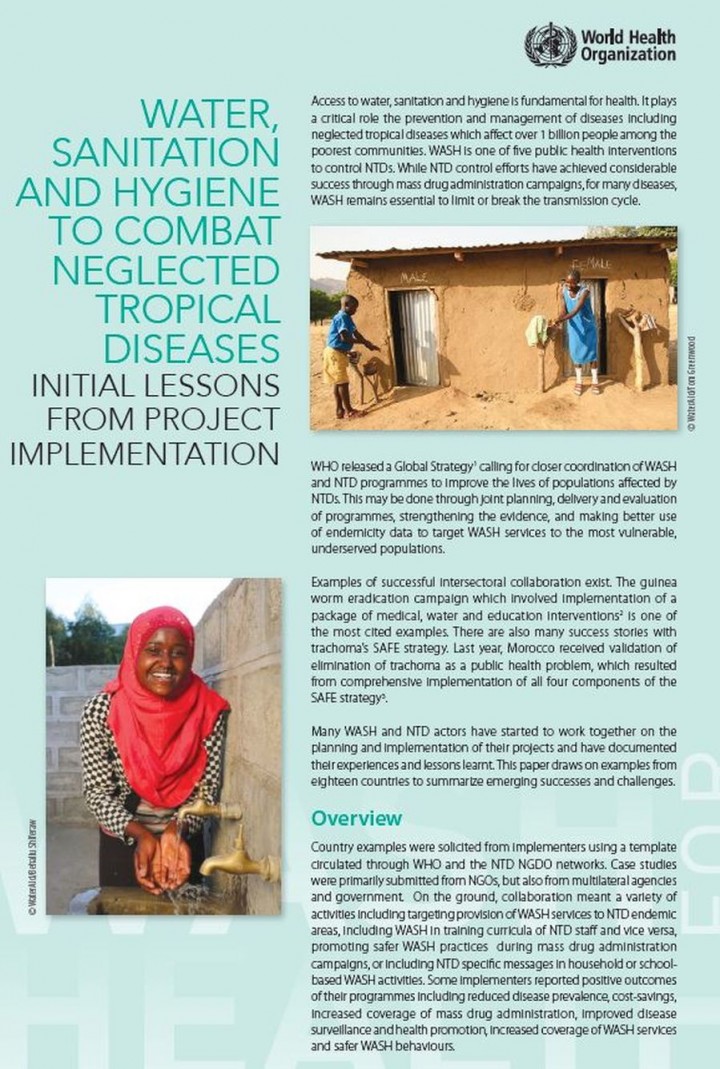

Lack of improved water sources, poor sanitation and hygiene expose billions of people, particularly children and the vulnerable, to a wide range of preventable diseases and are major contributors to the world’s morbidity and mortality. According to UNICEF and WHO a staggering 2.3 billion people do not have access to basic sanitation and 844 million people lack basic access to drinking water (WHO & UNICEF, 2017).

As a result of this situation, around 4 million people die from waterborne diseases every year. 2.2 million of these deaths are due to diarrhoea and 1.2 million of those are children under five. Malnutrition is the root cause of about 35% of all under-5 child deaths globally. It is estimated that 50% of these cases are associated with diarrhoea or with repeated intestinal worm infections caused by unsafe drinking water and/or poor sanitation and hygiene (WHO, 2008; Cochrane, 2008).

Diarrhoea is an aggravating factor in malnutrition, as it reduces the body’s capacity to absorb nutrients (leaky bucket syndrome). In addition, malnourished children are more likely to contract diarrhoea, as their systems are already weak, and the effect is cumulative.

The likelihood of mortality from diarrhoea when a child is severely underweight is almost 10 times higher than average (Black et al, 2008). The vicious circle created has a strong negative impact on child growth and development.

In the past years attention has focused a lot on diarrhea, as this is dramatic, measurable and episodic (Chambers, 2010). However, other faecally-related infections are often neglected and are very widespread such as Ascaris (1.5 billion), hookworm (740 million), Schistosomiasis (200 million) and liverfluke (40 – 70 million). These are often subclinical and less visible, less measurable, not episodic but continuously debilitating, and less treated.

Intestinal nematode infections like Ascaris and hookworm infections claim nutrients for themselves so that they are not available to be taken up by the human body. This issue has an impact on the long-term and causes chronic malnutrition. In addition, faecal bacteria ingested in large quantities by young children living in unhygienic conditions can lead to permanent gut damage which leads to nutrient malabsorption and consequently to undernutrition and stunting – a phenomenon known as environmental enteropathy (Humphrey, 2009).

The SuSanA Working Group on WASH and Nutrition will therefore also consider the impact that faecally-related infections other than diarrhea can have on the nutritional status of children and other vulnerable groups.

In the last few years a significant body of evidence suggests that poor WASH services also plays a considerable role in the increasing risk of sever acute malnutrition and stunting particularly among children. In the specific case of sever acute malnutrition an NGO examined the relationship between adequacy of water supply and children’s length of stay in a therapeutic feeding program in Niger. This study suggests that therapeutic feeding programs need to assure a good wash environment, in the target children’s villages, if they are to provide optimal care.

Consequently, this study highlights the causal link between WASH and Nutrition. The provision of safe water and sanitation coupled with improvements in hygiene (WASH) can hence contribute significantly to this nutritional challenge and to health improvements. Assuring access to safe water and sanitation and to good hygiene practices (e.g. handwashing) should thus be a key integrated element in all humanitarian responses to a nutritional crisis.

Objectives

Raise awareness for the links and opportunities for integration between WASH and Nutrition (including health and other relevant sectors) by providing space for practitioners to discuss experiences, best practices, research, challenges and gaps.

Activities

- Exchange on latest projects, research, guidance, policies, tools and events relevant to WASH and Nutrition and foster networking and collaboration among members to ensure capacity building on WASH & Nutrition integration.

- Develop a fact sheet (and keep up to date) on the link between WASH and Nutrition to be used by practitioners and policy makers.